4 Quality Assurance

Quality assurance activities are divided in:

- Static: activities that do not require code execution

- Code reviews

- Static analysis tools

- Dynamic: activities that require code execution

- Testing

4.1 Testing

In traditional software, we evaluate functional correctness by testing, that is, by comparing the actual behavior of software against the intended behavior. Each mismatch is considered a failure that is caused by a bug in the code. We don’t have tolerance for occasional wrong computations.

A ML model is an algorithm that has been learned from data, so we accept that we cannot avoid some wrong predictions. Model quality always refers to fit, not correctness: an evaluation will determine whether a model fits a problem and is useful for solving a problem. Evaluating model quality is ultimately a validation question rather than a verification question. Without a specification, we cannot establish correctness, but instead evaluate whether the model fits a user’s needs.

Measuring model quality for classification models: Accuracy, Recall, Precision, F1-Score, ROC-AUC, etc…

Measuring model quality for regression models: MAE, MSE, RMSE, etc…

Measuring model quality for ranking models: MAP@K, MRR, NDCG, etc…

Measuring model quality for generative models: BLEU, ROUGE, etc…

Performance measures in isolation are difficult to interpret, we need a baseline, that could be a very simple one, or the state of the art, if available.

To evaluate, we need to split the available data into training, validation, and test data, drawn from the same distribution, representative of the target distribution.

- Crossvalidation: repeated partitioning of data into train and validation data. Train and evaluate model on each partition, average results

- Split strategies: leave-one-out, k-fold

- Always test for generalization on unseen data

- Sign of overfitting: accuracy on training data >> accuracy on test data

The common pitfalls of evaluating model quality are:

- Out-of-distribution (OOD) data

- Using test data that are not representative

- Using misleading metrics (using accuracy with unbalanced datasets)

- Data leakage

- Normalization before splitting

- Dependence between training and test data (time-series data, multiple data points that belong together)

- Label leakage: a model picks up on subtle signals that leak the true label in the dataset

Measures about all test inputs can mask problems:

- Curate validation data for specific problems and subpopulations:

- Fairness and systematic mistakes: consider separate evaluations for important subpopulations

- expect comparable accuracy

- Validation datasets for important inputs

- expect very high accuracy

- Validation datasets for challenging inputs

- accept lower accuracy

- Fairness and systematic mistakes: consider separate evaluations for important subpopulations

- Create assertions for key slices

- Ensure that high priority slices of data continue to improve in performance

4.2 Behavioral testing

Behaviors can be seen as partial specifications of what to learn in a model for a problem. Behavioral testing uses dedicated test data specific to each behavior. Creating data for specific behaviors can be a way of encoding domain knowledge

We want to identify behaviors (capabilities) that we expect a model to learn as part of larger tasks of the model. An example in sentiment analysis: handle negation, robustness to typos, ignore gender, etc.

For each capability we create specific test sets (multiple examples).

We have three key types of behavioral tests:

- Invariance: changes in the input should not affect the output

- Directional: changes in the input should lead to predictable changes in the output

- Minimum Functionality: basic tests that the model should be able to pass

4.3 Data Quality

- Imprecise data (random noise) -> less confident models, more data needed

- Wrong manual data entry

- Unreliable sensors

- Wrong results and computations, crashes

- Inaccurate data (systematic problem) -> misleading models, biased models

- e.g., data from past biased decisions against minorities -> fairness issues

We can set some expectations on data quality:

- rows/cols: presence of specific features, and row count of samples

- individual values: individual values of specific features

- missing values

- type adherence

- values must be unique or from a predefined set

- list (categorical) / range (continuous)

- feature value relationships with other feature values

- aggregate values: all the values of specific features

- value statistics

- distribution shift

4.4 Testing Taxonomy on Granularity Levels

- Unit tests: test individual components in isolation (e.g., data preprocessing functions, model training functions)

- Integration tests: test interactions between components (e.g., data pipeline with model training)

- System tests: test the complete system end-to-end (e.g., end-to-end testing of data ingestion, model training, and deployment)

- Acceptance tests: validate the system against user requirements (e.g., does the deployed model meet performance criteria on real-world data?)

4.5 Online Tests

Here we do a mix of system and acceptance tests, we can do online tests in three ways:

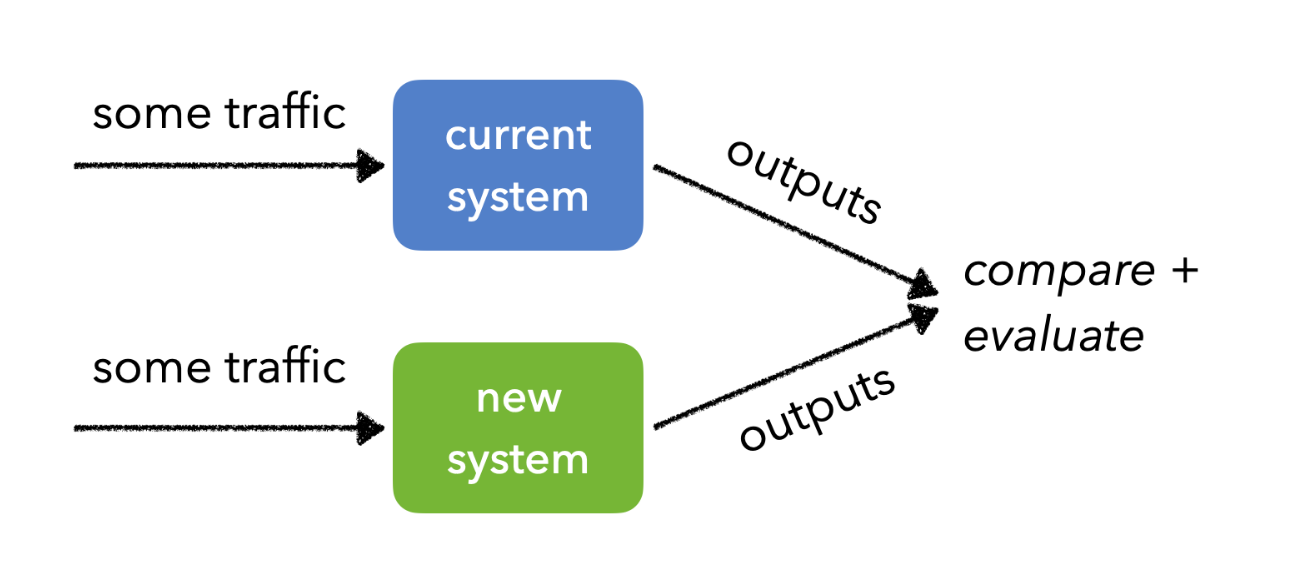

- A/B testing: compare two versions of a model or system by splitting traffic between them and measuring performance metrics

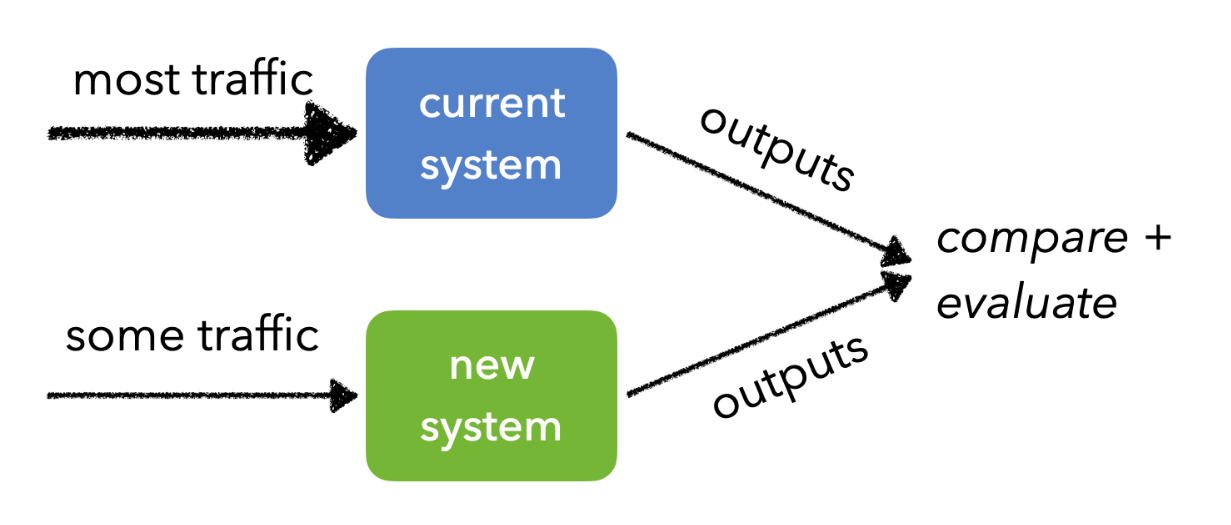

- Canary testing: deploy a new model to a small subset of users to monitor

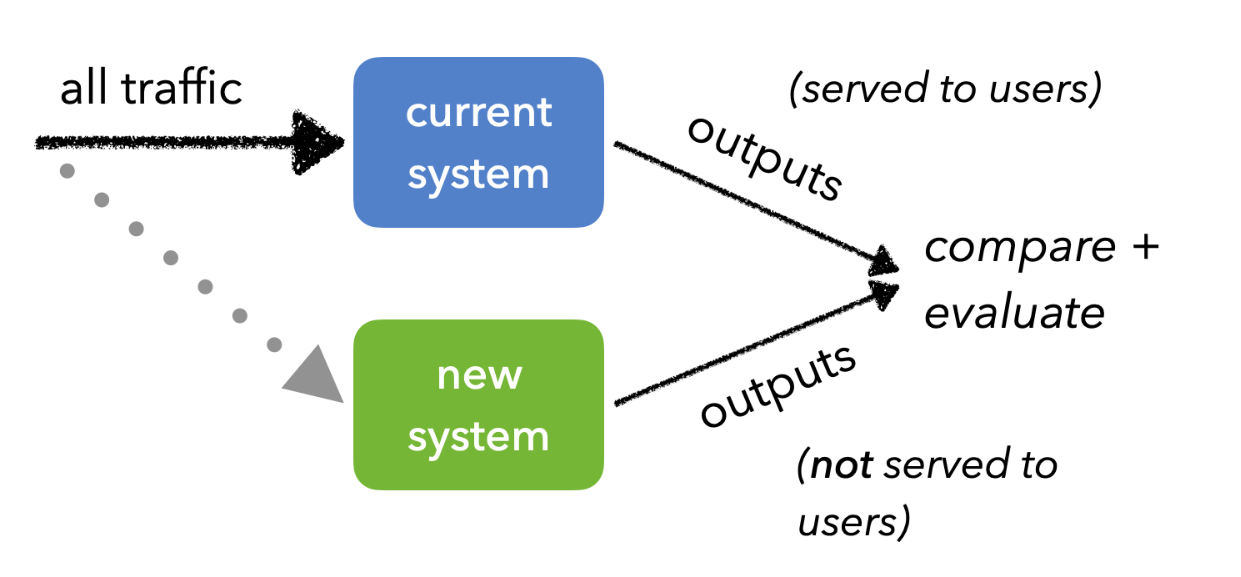

- Shadow testing: run a new model in parallel with the existing model without affecting user experience, to compare outputs and performance